Conor Harrington on ‘The Blind Exit’

In an exclusive interview by Dan Fontanelli for Atelier JI, Conor Harrington talks about the themes behind his latest edition, ‘The Blind Exit’, released by HENI. The edition is based on a mural by Harrington in Greenwich, an area famous for its maritime history and ties to British empire history.

-

It began with an oil painting, I painted an 18th Century kind of figure, a ‘man of importance’ sitting down on a chair, he’s got a globe beside him on a side table, but the globe was all wiped out, distorted, playing with the idea that maybe the rest of the world doesn’t matter so much anymore to certain people. And then down at his feet are two loudspeakers, I think in the run up to the referendum the role of fake news, right wing media and propaganda was quite deafening at the time, there was a lot of noise and a lot of lies.

I’m interested in the idea of being trapped by history which can happen and I think definitely happened with the Brexit referendum where there was a very strong sense of nostalgia and a pining for an imagined past going on. That really inspired me with this piece, I think, and that’s why the flag is blocking his view and blinding him, but it’s also about to smother him.

Greenwich is a great place to paint a mural because it’s a very historical part of London. It’s got the Cutty Sark and the Royal Naval College; it’s got so many ties to British history and the empire, so I was very excited and a little nervous if I’m honest to be painting my mural there. Again, I think people just saw a giant union jack and were mostly happy. [laughs]

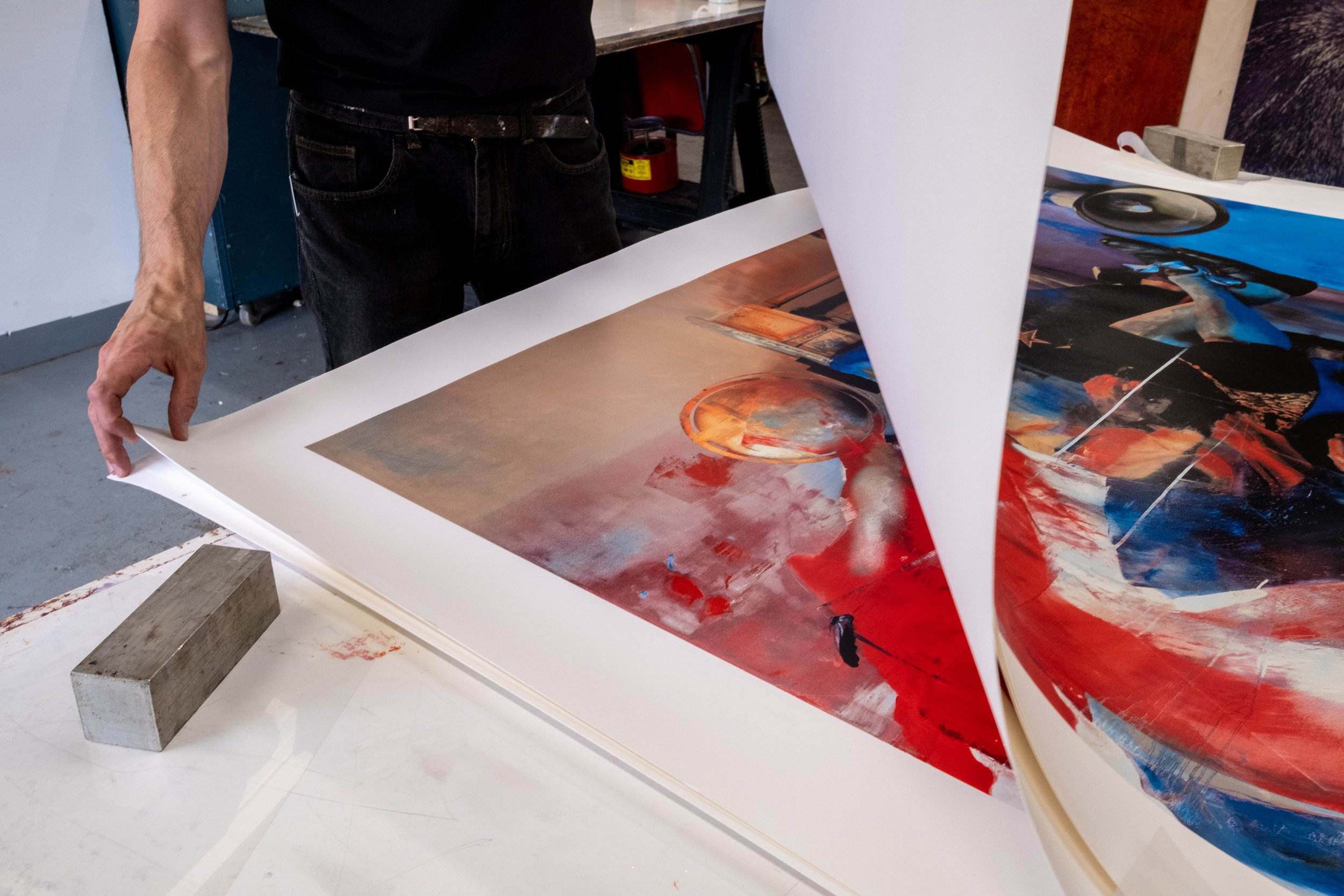

From a dimension point of view, [The Blind Exit] will be the biggest print I’ve ever done. I think it has to be large because there’s a lot of information in the painting, it just wouldn’t work on a smaller scale. There’s definitely various focal points, there’s a lot of chaos in there and a few nice little details that I always like to anchor the piece, like the ribbons, or the hand, or the flag, or there’s a little bit of pattern on his waistcoat that jumps out.

-

Dan Fontanelli: Hi Connor, could you tell us about the origin of the ‘Blind Exit’ edition?

Conor Harrington: It began with an oil painting, I painted an 18th Century ‘man of importance’ sitting down on a chair with a globe beside him on a side table but the globe was a sort of wiped out, distorted, playing with the idea that maybe the rest of the world doesn’t matter so much anymore to certain people. And then down at his feet are two loud speakers, I think on the run up to the referendum the role of fake news, right wing media and propaganda was deafening at the time, there was a lot of noise and a lot of lies.

There’s been a lot of flag waving I think, I think that’s what’s been interesting, and its been echoed on both sides of the Atlantic with the Trump election in 2016 and the Brexit Referendum in 2016, and there’s been a lot of joking about the special relationship but I definitely think both countries were waving a lot of flags at the time and that definitely had a big impact on the work I was making.

Dan: What was the first work or art that made you realise you could have a political voice within the arts?

Conor: I guess it began with a lot of the early hip hop I was listening to was quite political, the very first rap I got into was Public Enemy, and then after that it was Ice Cubes The Predator album which was a response to the Rodney King beating in LA and that really stuck me. The music was something that I really enjoyed, but as a 13 year old living thousands of miles away it was something educational and informative. So from then I really liked that marriage of aesthetics and style with a strong message as well. I guess street art has always been political, graffiti is a very political act, my own work early on was probably a lot less political but as I get older the ideas are coming to the fore a lot more. I’ve always tentatively been playing with the ideas of politics, masculinity and empire but in the last few years its been coming g out in my work a lot more clearly I think.

Dan: When you look at the murals on the side of building your figures are ghostly, painted so they appear and disappear, seemingly trapped in a cycle of repeating the same action or gesture. How did this style evolve?

Conor: I’m very interested in the cyclical nature of power and politics and ego and all these things. Nothing lasts forever and I’m very interested in the downfall of the so called great and the good, so I think that feeds into the way that I paint, the feeling of pain and erasure, putting the paint one and taking it off. And that goes back to earlier work that I was doing that was responding to painting graffiti and then the council removing it, so that’s where I started the swipe thing that I do, putting solvents on the canvas and removing paint, and it relates to these figures, their downfall eventually come round and I’m trying to convey some of those idea in the way that I paint.

Dan: How did you discover graffiti / street art?

Conor: I went to school in Cork and there wasn’t much of a street art scene at the time, there was a little bit of tagging and a few wall pieces but I saw my very first piece in a National Geographic magazine before I’d seen anything in real life and that really jumped out at me, it was a piece that said City Of Fallen Angels, I presume it was in LA I’ve got no idea who the artist was and I realised this was connected to the new music I was discovering. So I practiced bubble letters for a couple of years before I bought my first can of spray paint I tried it outdoors for real. So there’s wasn’t much of a scene going on until a few years later so it was a very slow isolated process which is possibly different to a lot of other graffiti writers early learning experiences anywhere else I think.

Dan: Did the famous murals of Northern Ireland influence you when you were growing up?

Conor: I few years into starting graffiti my uncle went up to Derry and when he came back gave me copies of his photos and that was the first time I’d seen them, this was before the internet and even though Derry was only 300 miles away it felt like a world away and yeah, I was definitely blown away by them.

Dan: Costume in your work is distinctly 18th century, even though your confronting contemporary issues, is this a way of saying things haven’t changed or are you siting the origin of the problem?

Conor: It’s very over the top and in a way reminds me of the fantastical elements you find in hip hop to a degree, just the idea of fantasy and make-believe kind of elevating your status above what you are. It creeped in slowly I guess, my dad was really into history, so I grew up around a lot of history books, I wasn’t such a big fan of reading them but I enjoyed looking at the pictures! So I think that kind of aesthetic was ingrained in me from an early age, and when I got older and went to art college and started to learn about art I was quite taken by the renaissance and then I wanted to try and find some way to intergrate that into graffiti so how do they work together or do they work together, I had no idea. But it also related to my own experiences at art college where I felt that graffiti and street art wasn’t necessarily respected and I felt the art establishment didn’t respect graffiti, so at the beginning this costume versus the tags was a dialogue between the art establishment and all of us who grew up painting on the streets.

Dan: When I see the hand grasping the chair in this work and the position of the figure I’m reminded of Velazquez’s & Bacon’s, Pope Innocent paintings. I kind of imagine that face under the flag. Were those works an influence?

Conor: It wasn’t a conscious decision, but there’s a big chance that those works did creep in subliminally, I think there’s a kind of similar stress going on in both figures, in my painting the guy is sitting on the chair with the flag in front of him and he’s not at ease, kind of being smothered by the flag. I’m interested in the idea of being trapped by history which can happen and I think definitely happened with the Brexit referendum where there was a definite sense of nostalgia and a pining for an imaginary past going on.

“I’m interested in the idea of being trapped by history ... [during] the Brexit referendum there was a very strong sense of nostalgia and a pining for an imagined past going on. That really inspired me with this piece, I think, and that’s why the flag is blocking his view and blinding him, but it’s also about to smother him.”

The Blind Exit

2023

1250 mm x 995 mm

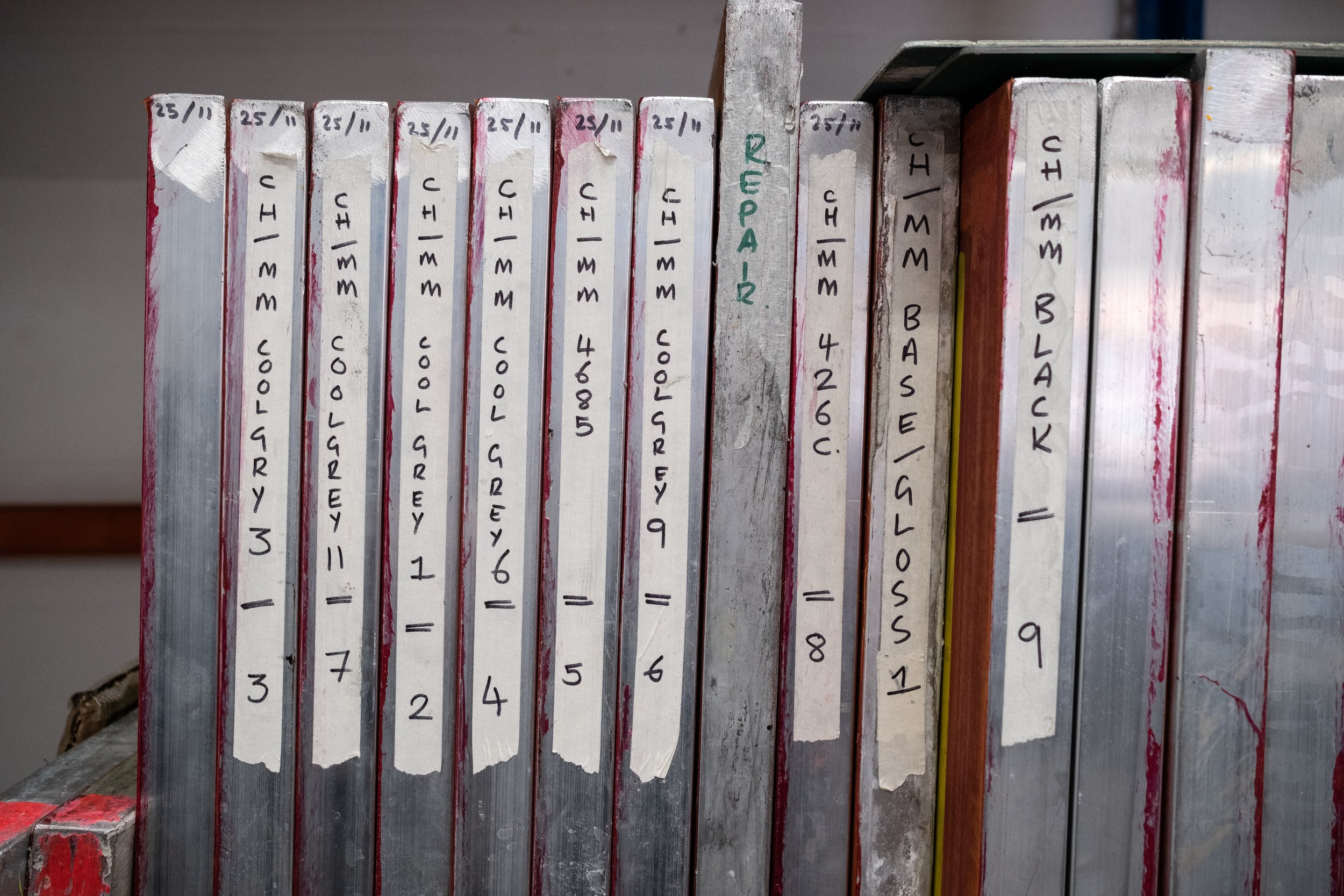

Silkscreen print in 28 colours with high gloss varnish on Somerset Satin Cotton

Edition of 100

Published by HENI

For more details about ‘The Blind Exit’, visit heni.com

Film courtesy of Dan Fontanelli